Ejaradini

Ejaradini seeks to think through South Africa’s colonial gardening inheritance – particularly how gardening has been reimagined by Black South Africans – to model onto the inheritance of museums. . Black urban gardening is an existing practice that takes the colonial inheritance and remakes it, creating a very different set of implications and practices that are of deep value to thinking about what decolonisation might mean, especially for museums.

To live in the post-colony, and to be dedicated to a decolonising process, is to be burned by the question of what to do with one’s colonial inheritances. Throughout the African continent, infrastructures, practices and epistemes have been left behind by colonial powers and in various ways, their powers remain. Should they be torn down? Left to rot? Reinforced? How, through what processes, and by whom? And how do we decide? When thinking of how to deal with colonial inheritances, we might learn from existing practices and models from ordinary black life that offer some possibilities.

The project Ejaradini by Johannesburg based collective MADEYOULOOK, sought to think through gardening to potentially answer some of these questions. Gardening is a colonial imposition with colonial implications. Its history, as we know it globally today, is deeply informed by a colonial period and its inherent episteme. This includes practices of collecting from far off lands during colonial expeditions, obsessions with the exotic, assumptions of ‘colonial man’s’ right to control and structure his environment, the role of knowledge accumulation in power, the naming and categorising of objects as part of this power dynamic and the imposition of European structures, positions and even plants/lawns in environment where they do not belong. As you might note, these characteristics map almost identically onto museums which have historically been spaces of collections, exoticism, control, categorisation and the inherent power dynamics of this kind of knowledge production. These two practices reach their modern zenith through colonialism and in many ways represent its key problematics.

The Ejaradini project therefore, seeks to think through this gardening inheritance – particularly how gardening has been reimagined by Black South Africans – to model onto the inheritance of museums. Black urban gardening is an existing practice that takes the colonial inheritance and remakes it, creating a very different set of implications and practices that are of deep value to thinking about what decolonisation might mean, especially for museums. The Ejaradini project sought out archives of black gardening in South Africa, and found primarily photography archives spanning from the 1950s to the present. Through the archive and further research, it was possible to determine a number of ways in which Black urban gardening refigures this inheritance:

Place and belonging making

The photography archives point to the growing of substantial gardens in the period prior to, during and after the forced removals. To plant a garden is to make an investment in the future, to believe that one will remain in one place to experience the change in seasons. To plant a garden in the midst of forced removals is therefore a radical statement of belonging making, it is to say, defiantly, that one ‘will not move’.

De-alienated labour and a radical repossession of time

To grow a garden in this period is also to invest one’s time and labour in one’s own pleasure and return. The garden becomes a site outside of the migrant and exploitative labour regimes that removed so many black South Africans from the potential of their labour, but also resulted in limited time for leisure or self-investment. The garden then is a claim to time and labour for the self. Importantly this time is also not industrial time, but time of the rains, of sunlight and of the seasons. This is a time not owned by the powers of capital.

Domestic authority

The home garden also becomes a space of domestic labour of pleasure. The domestic becomes the site of productivity but also of leisure and enjoyment. This domestic space is also not necessarily gendered as both men and women were often responsible for caring for their gardens (in opposition to the garden boy determination of white suburbs). The garden therefore becomes a space of claiming the power of the domestic, of intimacy and home-ness.

Refuge and sanctuary

This domestic power, and the pleasure it generates, also speaks to a sense of refuge and sanctuary that the black urban gardens make possible. The meditative labour of gardening, the intimacy and care that they engender creates the potential of a safe space specifically for enjoyment and selfhood.

Death and rot

Very importantly these elements of the garden are not utopic, but rather part of a natural cycle of time that includes death and rot and change. The garden and the plant world more broadly also offer us the potential for what emerges when we let things die, and what might grow out of the things that must end.

The Ejaradini project sought to encourage a modelling of these elements onto the museum. The installation was primarily a garden made up of plants found in township gardens, considered to be plants of sustenance, spirituality, healing and even ‘just’ of ornamental value. Interspersed in the garden were the photographic archives, referencing the long tradition of this practice. The garden, built in the courtyard of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), was created as a space of pause and rest, a refuge in the midst of the mad city. But importantly it was also developed to encompass a range of programming, including a children’s gardening programme, collaborations with black urban growers, a talks programme and events for a variety of other practices including a poetry recital and even the JAG Christmas party. The garden was therefore intended to be a space that introduced socialities to the museum. The garden made tangible; pleasure, leisure, refuge and time to pause outside of the conventions of usual museum practice. The garden brought together people who otherwise didn’t use the space, encouraging the use of the museum not simply as a space of quiet collection and contemplation of objects, but also the creation of meaning and connection to other kinds of labour. The garden sought to make practical, the ways in which the death of the colonial museum might serve as the rot that feeds other relations.

Based in the busy inner-city of Johannesburg, the JAG sits as a heavy and challenging colonial inheritance, struggling to find its place in contemporary South Africa. This burden of colonial power and violences seems almost unable to shake off the implication of its past. But through ordinary everyday black life we might find ways in which people have challenged the colonial in powerful and often quite simple ways, and we might learn from their finding pleasure and rest even in the heart of colonial infrastructures. We might begin to imagine what decolonisation can be.

First appeared: Latitudes

See also articles in Vuvuzela and Bubblegum Club

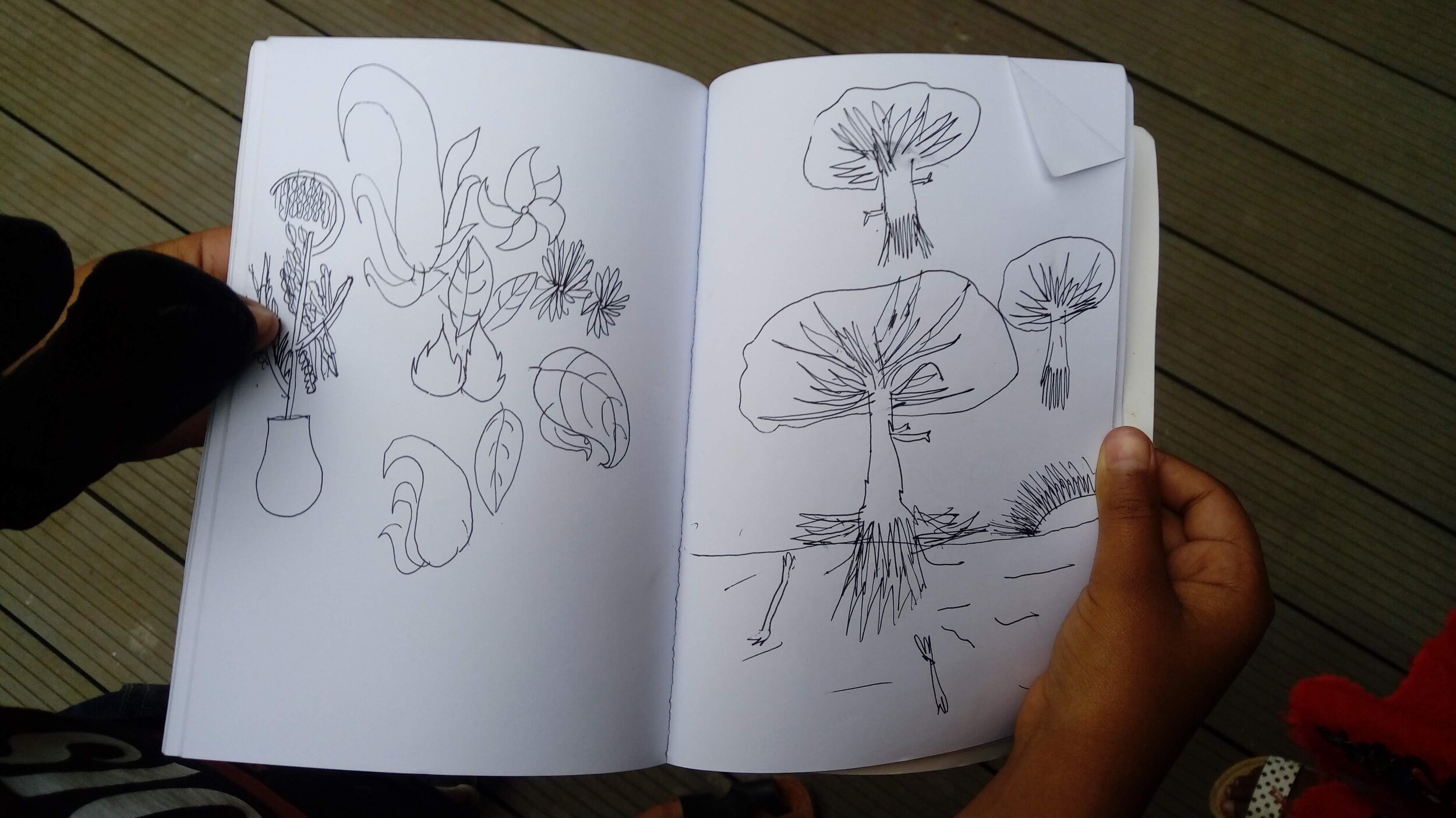

Young People’s planting programme with local students at Ejaradini with Sun Mabengeza and Colin Groenewald